The Rise of Financial Exploitation in the New Age Movement

- Anna Eliza Predoiu

- Aug 26, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 27, 2025

Defining New Age Spirituality

Springing up in Western pop culture in the 1970s, the New Age Movement and esotericism propagated through a mix of spiritual practices that go far beyond the existing major religions like Christianity, Judaism, and Islam (Carnevale & Nowaczyk, 2023). Defining this movement is challenging, as people in this spiritual scene draw their beliefs from a range of traditions, styles, and ideas (Aupers & Houtman, 2007). New Age spirituality tends to emphasize the healing powers of nature, the presence of a higher power, the existence of destiny, and the notion that everyone is connected, all while challenging traditional religious authority (Thompson, 2023).

Where Spirituality Intersects Commerce

A cycle of financial dependency and manipulation exists at the intersection of economics and some religious groups. This concept is deeply rooted in the mass commercialization of religion. In their search for spiritual guidance or fulfilment, some people who reject mainstream religious practices might fall into similar dynamics when seeking alternative spiritual paths.

There exists notable historical instances of said dynamics. The Moonies, or the Unification Church, is a religious movement founded in 1954 by South Korean Sun Myung Moon. The Church gained notoriety in the 1970s for its intense recruitment tactics targeting young people and getting them to work long hours in businesses connected to the Church with little to no pay (Melton, 2024b). Their followers were also pressured into donating large sums of money to the institution, which left many financially drained (Kilbourne, 1986).

Similarly, in the 1980s, the Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh created a religious commune, gathering thousands of devotees, in the Oregon Desert (Urban, 2018). The affair quickly went south as his followers were encouraged to give up their finances and personal belongings to support the movement. At the time, Rajneesh generated the biggest wiretapping case in U.S. history, the largest case of marital immigration fraud ever historically recorded (Keyser, 1985), and the largest salmonella-induced bioterrorist attack in the U.S. (Urban, 2018).

However, the most notable example of this phenomenon remains Scientology, an international movement that was created in the 1950s by the science-fiction author L. Ron Hubbard (Melton, 2024a). This set of beliefs, which poses as a religion, focused initially on taking advantage of people’s mental struggles. Scientology uses a method they refer to as “auditing,” an unregulated version of counselling that charges users around $800 an hour (Nededog, 2016). The “E-meter,” created by Hubbard, is the tool used by auditors to measure a person’s engrams, defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “hypothetical changes in neural tissue postulated in order to account for persistence of memory” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Hubbard claimed this tool could locate traumatic memories, which would then be “erased” through the process of auditing. Hubbard also claimed the e-meter could cure blindness and improve intelligence as well as appearance (Behar, 1991). This practice is still in use.

Drawing from these historical occurrences, many might confuse true spirituality with spiritual materialism (Gould, 2006), a term coined by the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chögyam Trungpa in the 1970s. The term suggests that Westerners use such spiritual practices to boost their egos, rather than to truly change and grow. This therefore enables major retailers, self-proclaimed gurus, healers, and witches to sell everything from enlightenment to magical objects or even miraculous healing. They achieve this mainly through the commodification of spirituality and the strategic use of social media marketing to exploit people’s vulnerabilities (York, 2010).

The Commodification of Spiritual Practices

Commodifying refers to the process of turning something that has no inherent economic worth into something with monetary value. This oftentimes comes at the expense of other social values (Levesque, 2016). In this context, it can manifest itself as cultural and spiritual appropriation for profit, with traditionally Indigenous practices being frequently targeted.

Notably, white sage, a plant historically and culturally deeply sacred to First Nations and Métis Peoples of North America (California Native Plant Society, n.d.), is now the target of overexploitation and a prominent example of commodification. Rangers at North Etiwanda Preserve near Los Angeles often catch people illegally harvesting large quantities of the plant (Hay, 2022). Over the past five years, rangers have seized up to 20,000 pounds, sometimes up to 1,000 pounds of sage per trafficker (California Native Plant Society, n.d.).

The rising demand for white sage, driven by New Age beliefs about its cleansing and calming properties, has greatly appropriated and misrepresented Indigenous traditions. The sage is decorated, packaged, and sold as “smudge kits.” These kits can be found on major multi-billion dollar retailer websites such as Amazon, Etsy, Alibaba, and Walmart. The poaching is often done by undocumented workers, making a few pennies per brush, while the middlemen rack up $30 to $50 per pound (California Native Plant Society, n.d.). This process disrupts the ecosystem, commodifies the Indigenous tradition, and exploits vulnerable labourers in the name of profit.

Within the same context, ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic tea with a strong religious and medicinal significance, has similarly become a commodity in the global wellness and spiritual tourism industry (Babe, 2016). The Indigenous Peoples of South America, specifically of Amazonia, have been consuming this tea during rituals for thousands of years (Walubita, 2020). Western interest in ayahuasca has surged following stories shared by celebrities like Miley Cyrus, Machine Gun Kelly, and Jim Carrey. Countless influencers and participants brag about their experience of enlightenment or spiritual awakening while consuming the drug in private retreats. For the everyday attendee, the cost of these retreats range from the low-end of $1,200 weekly to over $4,000 for a high-end experience (Refugio Altiplano, 2024).

Goop, Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness brand, featured an article promoting an ayahuasca retreat experience in the Amazon rainforest, where the costs ranged from $4,000 to a whopping $18,000 weekly (Jaeger, 2022). The belief in the authenticity of these ayahuasca rituals and of the ‘shamans’ that lead them is often misleading and dangerous. Indigenous populations believe the use of ayahuasca helps communication with ancestors to access their knowledge and wisdom (Walubita, 2020). In contrast, many Westerners use ayahuasca as a tool for personal transformation and spiritual awakening. This perspective commodifies the ritual, as tourists are willing to spend exorbitant sums of money to partake in these various inauthentic, unregulated retreats in South America. This practice is turning the Indigenous tradition into another trendy wellness and ‘psychedelic’ experience.

Predatory Advertising

Vulnerable people are often preyed upon and become the target of easy manipulation by marketers charging excessive fees for services that offer little more than just empty promises.

The idea of the Law of Assumption, a concept stemming from the late 20th century, rose to fame during the pandemic, a time when the population’s morale was at a record low. Determining whether the principle is true is more complex than defining it. The Law of Assumption states that whatever someone believes is true will become their reality. For instance, Pinterest, a billion-dollar social media platform, recorded a 54-fold increase in searches for "manifestation techniques," seeing their profits rise tremendously in the Q4 of 2020 (Bellan, 2021). The idea that you can manifest success, love, or money is certainly appealing. Many struggle to manage negative thoughts and maintain a positive outlook, creating an ideal opportunity for 'gurus' and 'coaches' to market training programs promising to help individuals achieve their dreams through the power of thought. TikTok and Instagram have become breeding grounds for hundreds of these unregulated coaches who charge hundreds or even thousands of dollars for services and advice that often prey on people’s desperation.

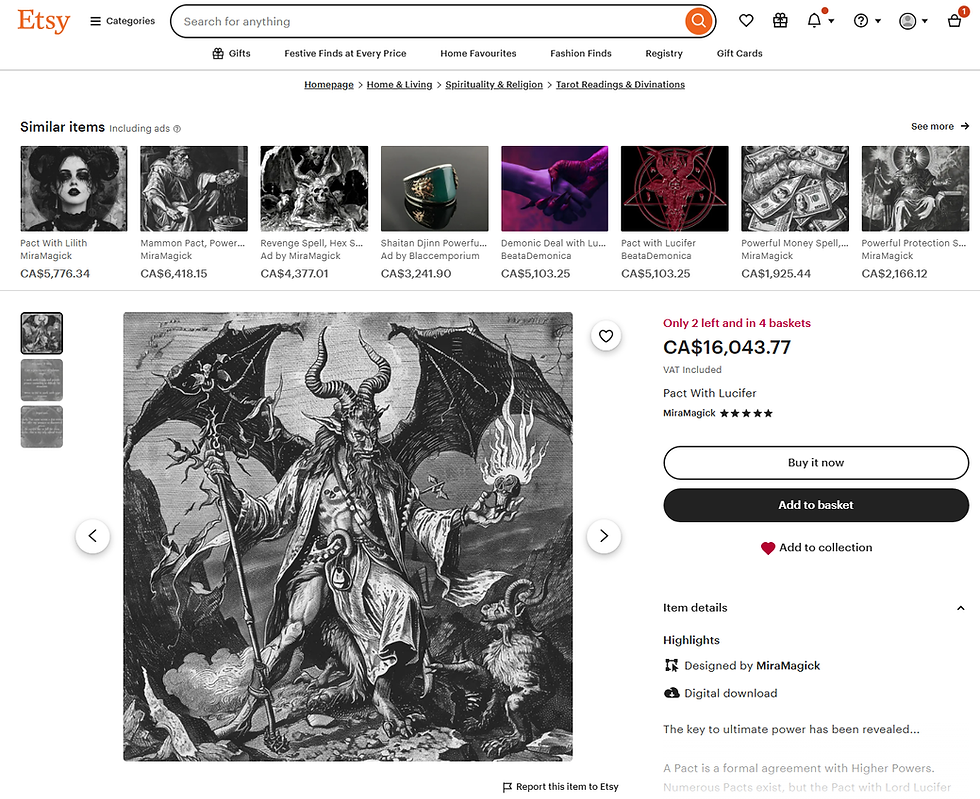

Another of the most prevalent tactics is “spell work” performed by witches who promise unrealistic and potentially dangerous outcomes. The search for the word “spell” yields over 20 pages of results and more than 1,000 listings on Etsy, a popular online marketplace. The variety in this market is representative of the lengths sellers will go to generate quick profits. A $1,200 “professionally” performed spell guarantees the buyer a pact with Mammon (MysticZahraSpells, Etsy), the biblical demonic deity personifying wealth, and is designed to attract riches. Ironically, since the 16th century, Mammon has negatively represented the pursuit of wealth in both religious and secular contexts (Petruzzello, 2024). Taking this idea further, one seller offers a deal with Satan for $16,000 (MiraMajick, Etsy).

More notably, a spell sells the promise of bringing back a loved one from the dead for a week, priced at $600, “generously” reduced from its original price of $1,200 (Valandor, Etsy). These online stores are not just for show as they often garner many sales and numerous positive five-star reviews. Etsy’s platform allows the sale of these spells for a cut of the profit, as they pocket a minimum of 6.5% of each transaction (Etsy Help Center). These tactics may seem like an obvious scam to some, but, for the buyers, it can feel like a last desperate resort. In a moment of hopelessness, individuals may gamble their last dollars on these spells and workshops, oblivious to what they are purchasing.

A Conclusion to the Commercialization of Spirituality and Its Impact

The verdict of the commercialization of religion and spirituality in the New Age movement is clear. Vulnerable people are consistently being taken advantage of, under false guarantees and commodification of spirituality. People are promised quick fixes, spiritual awakenings, and personal transformation, only to find themselves financially and emotionally drained.

The idea that this cycle of exploitation will end in the future is appealing. However, it is an issue that has persisted through time. Humans naturally seek purpose and meaning to life. It is important to stay informed on ongoing and historical issues surrounding the commodification of spirituality to know how to spot the difference between real and fake spirituality. By questioning what is being sold to them, individuals can avoid falling into the same traps.

References

Aupers, S., & Houtman, D. (2006). Beyond the spiritual supermarket: The social and public significance of New Age spirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 21(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537900600655894

Babe, A. (2024, August 9). Ayahuasca tourism is ripping off Indigenous Amazonians. VICE. https://www.vice.com/en/article/ayahuasca-tourism-is-ripping-off-indigenous-amazonians/

Behar, R. (1991b, May 6). The thriving cult of greed and power. Scientology: The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power. https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Fishman/time-behar.html

Bellan, R. (2021, February 17). Pinterest search trends for ‘manifestation,’ ‘self-love’ increase amid pandemic. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccabellan/2021/02/17/pinterest-search-trends-for-manifestation-self-love-increase-amid-pandemic/

California Native Plant Society. White sage protection. California Native Plant Society. (2024, January 10). https://www.cnps.org/conservation/white-sage

Carnevale, J., & Nowaczyk, J. (2023, November 21). New age movement | Region, spiritually & characteristics. Study.com. https://study.com/academy/lesson/new-age-movement-spirituality.html

Etsy Help Center. (n.d.). Etsy fee basics. https://help.etsy.com/hc/en-us/articles/360035902374-Etsy-Fee-Basics?segment=selling.

Gould, S. J. (2006). Cooptation through conflation: Spiritual materialism is not the same as spirituality. Consumption Markets & Culture, 9(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253860500481262

Hay, M. (2022, April 1). How the rage for sage threatens Native American traditions and recipes. Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/white-sage

---. (2020, November 4). The colonization of the ayahuasca experience. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-colonization-of-the-ayahuasca-experience/

Jaeger, C. (2022, May 1). “The unparalleled greatest feeling”or risky drug? Inside the celebrity-loved psychedelic. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/health-and-wellness/the-unparalleled-greatest-feeling-or-risky-drug-inside-the-celebrity-loved-psychedelic-20220331-p5a9oa.html

Keyser, C. (1985, December 13). Five Rajneeshees plead guilty to immigration fraud. UPI Archives. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1985/12/13/Five-Rajneeshees-plead-guilty-to-immigration-fraud/9486503298000/

Kilbourne, B. K. (1986). Equity or exploitation: The case of the Unification Church. Review of Religious Research, 28(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.2307/3511468

Levesque, R.J.R. (2015). Commodification. In: Levesque, R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32132-5_790-1

Melton, J. G. (2024, October 29). Scientology. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Scientology

---. (2024b, October 19). Unification Church. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Unification-Church

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Engram. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved November 18, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/engram

MiraMajick. (n.d.). Pact with Lucifer. Etsy.com. https://www.etsy.com/ca/listing/1812003665/pact-with-lucifer?click_key=998659aab69a21d3ae345a19a6ad5111b78a8bec%3A1812003665&click_sum=fb5214ef&external=1&rec_type=cs&ref=landingpage_similar_listing_top-5

MysticZahraSpells. (n.d.). Powerful riches pact with Mammon, ultimate wealth spell, demon pact ritual. Etsy.com. https://www.etsy.com/ca/listing/1786082016/powerful-riches-pact-with-mammon?ga_order=price_desc&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=spell&ref=sr_gallery-20-1&dd=1&content_source=edc944e7fe0534127c69e0d8b14435aa8dd701d2%253A1786082016&search_preloaded_img=1&organic_search_click=1

Nededog, J. (2016, December 14). How scientology costs members up to millions of dollars, according to Leah Remini’s show. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/scientology-costs-leah-remini-recap-episode-3-2016-12

Petruzzello, M. (2024, September 19). Mammon. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/mammon

Refugio Altiplano. (2024, March 18). Cost of ayahuasca retreats in Peru: What to expect. Ayahuasca Retreat in Peru. https://www.refugioaltiplano.org/blog/2024/03/08/how-much-does-an-ayahuasca-retreat-in-peru-cost/

Thompson, K. (2023, October 3). What is the New Age Movement? ReviseSociology. https://revisesociology.com/2018/09/25/new-age-movement-what/

Urban, H., Robinson, M., Smith, E. A., & Lambert, C. (2018). Rajneeshpuram was more than a utopia in the desert. It was a mirror of the time. National Endowment for the Humanities. https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2018/spring/feature/rajneeshpuram-was-more-utopia-desert-it-was-mirror

Valandor, E. (n.d.). Phoenix resurrection spell bring the dead back to life. Phoenix Resurrection Spell Bring the Dead Back to Life - Etsy Canada. https://www.etsy.com/ca/listing/1768347638/phoenix-resurrection-spell-bring-the?ga_order=most_relevant&ga_search_type=all&ga_view_type=gallery&ga_search_query=bring%2Bback%2Bthe%2Bdead&ref=sr_gallery-1-6&pro=1&sts=1&dd=1&content_source=c11721a40b9bd4e65c9b5332bfadfb1a2e1b3d0d%253A1768347638&search_preloaded_img=1&organic_search_click=1

Walubita, T. (2020, February 21). Cultural context and the beneficial applications of ayahuasca. Lake Forest College. https://www.lakeforest.edu/news/cultural-context-and-the-beneficial-applications-of-ayahuasca

York, M. (2001). New Age commodification and appropriation of spirituality. Journal ofContemporary Religion, 16(3), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537900120077177